I became a Jew on the day I was born, December 17. Thirty-eight years had passed between the moment my mother gave birth to me in Romania and the day I was formally accepted as a Jew by rabbis in a North American synagogue.

After I’d completed a year of study, my mentor rabbi informed me that I was ready to take the next step toward conversion – writing a formal essay explaining why I wanted to embrace the Jewish faith, and meeting with a Beit Din. For those reading this who are unfamiliar with the term, a Beit Din is a rabbinical court assembly made up of three observant Jews (at least one of whom is a rabbi) who decide if a convert is fit to be accepted for conversion to Judaism.

Embracing Judaism was the last step along a journey of self-discovery that had taken me many years to explore, and I wanted to do this right – it was important to me that I should have a conversion process that followed the halacha (Jewish law) closely, which meant having a Beit Din made up of at least one rabbi, followed by a ritual immersion in a synagogue mikvah – a pool of water derived from natural sources.

It was the beginning of December and with my birthday right around the corner, it was only natural that I would schedule my Beit Din and Mikvah day on my birthday. How could I choose any other date? What better day to experience a spiritual rebirth and be formally acknowledged as Jewish?

The sun was shining brightly when I woke up early in the morning – too early in fact. The excitement and nervous butterflies churning in my stomach made it impossible to go back to sleep. ‘This is the last day I’ll wake up and not be Jewish,’ I thought. I busied myself by having a long shower, brushing and flossing my teeth, washing my hair and scrubbing my fingernails and toenails free of any traces of nail polish – there was to be no barrier between the body and the Mikvah water.

Brilliant sunshine illuminated the path toward the Beth Hillel synagogue where I would be formally interviewed. I knew it would be a beautiful day, and it turned out exactly as I’d imagined – how could such an important day ever be shrouded in clouds?

The rabbis met me in the lobby of the synagogue at noon. My Beit Din was composed of three ordained rabbis, all active members of the Rabbinical Assembly, although one had retired from his congregation. After everyone arrived, we walked over to the meeting room in the back of the synagogue. A long conference table split the room which could have seated twenty. The three rabbis sat on one side of the table, and I took a seat across from them.

“As we begin, I’d like you to tell us what brought you here and why you want to become Jewish,” Rabbi Levine said.

I summarized some of the key points that I wrote about in my conversion essay:

“The feeling that propels me toward Judaism isn’t as simple as breaking it down into words. It’s a feeling, an echo of something within myself that I am just now recognizing and giving voice to.

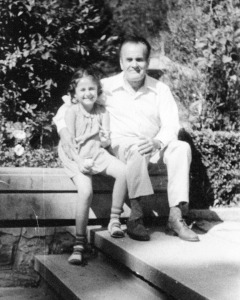

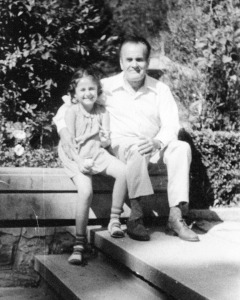

I feel that I have always been a Jew. I was born in the mid-1970s in communist Bucharest. Under Ceausescu’s dictatorship, Romania didn’t prioritize religion, choosing instead to indoctrinate their people to worship the State. I don’t remember either of my parents being religious in any way. We never went to church. I identified with my father’s family much more than my mother’s side. I stood out among my maternal cousins by being the black-haired, dark-eyed child who didn’t fit in. People said that my father and I ‘looked Jewish’.”

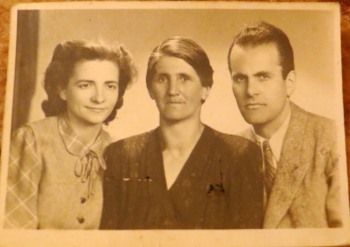

Above: me at age 11. Centre: my father Iosif (Josef) at age 15. Right: My father and grandmother Ana.

We emigrated to Canada when I was 11 years old. My father subsequently decided to return to Romania and died there when I was 13. I never had the opportunity to ask him all the questions I would have liked to know – Why did he hide his own heritage? Why did he feel ashamed of who he was?

I’ve had people tell me, Why bother to convert. Your father was a Jew, you don’t believe in Jesus as the messiah, so what’s the difference? But it bothers me that I am not recognized by all Jews as a fellow Jew because of my patrilineal descent, and I feel the need to undergo this formal process so that I can both learn much more about Judaism, and to feel like a “real” Jew.

In my soul, heart and mind, Judaism is more than a religion for me. It’s a shared history, a family and a connection that has always been there, just outside the realm of my consciousness and yet was always there. Like a pulse that cannot be subdued.

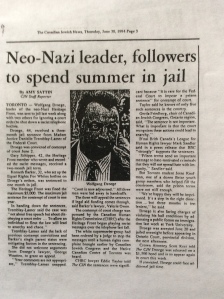

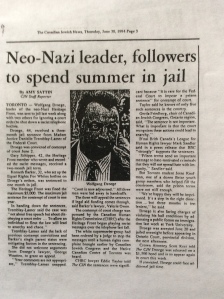

After my father’s death, I lived in a rough low-income neighbourhood with my mother. As time went by, she grew increasingly abusive and I had no choice but to run away. Between the ages of 14-16 I lived in several Children’s Aid homes. In time, I ran away from an abusive foster home and returned to my mother’s apartment. At age 16 I was friendless and desperate. Eventually I became recruited by a neo-Nazi group, the Heritage Front. They became the family I felt I’d never had, and looked after me at a time when my only choice was to live on the streets. They also put me in touch with an internationally-renowned Holocaust revisionist and Hitler sympathizer, Ernst Zundel. Zundel gave me a job working in his basement printing press, fed me and looked out for me.

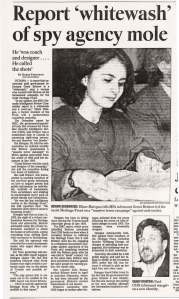

By the time I turned 18 I knew that what the group was doing was wrong. I wanted out of the organization but they were possessive of me and I didn’t know of a way out. I attempted suicide and eventually I turned to an anti-racist activist, who put me in touch with the director of a think-tank on extremist right-wingers. He, in turn, asked me to spy on the Heritage Front and Ernst Zundel and collect information that could be turned over to the police.

For half a year I gathered as much information on illegal activities, weapons and dangerous persons, as well as stole Ernst Zundel’s national and international mailing list, which consisted of people all over North and South America and Europe who had sent in money to fund Zundel’s Holocaust revisionist projects. In 1994 I testified in court and sent 3 Heritage Front leaders to prison, effectively dealing a serious blow toward dismantling the group.

I was only 19 years old. I lived in hiding and attended university in Ottawa under an assumed name. Upon graduating Magna cum Laude with a Criminology and Psychology double-major, I taught ESL in Seoul, South Korea and subsequently travelled throughout Europe the following year.

I spent some time in Krakow and visited Auschwitz and Birkenau. Something stirred in me that summer – an inexplicable familiarity, a sense that I was connected to those places in some undefinable way. When I first heard Ladino songs, it was as though I could almost recognize them. The music seemed familiar somehow. Then there were the places in the south of Spain, as well as in Poland and Hungary that I visited – they felt as though I’d been there before. In Debrecen, the city my father was born in, I allowed my feet to take me where they wanted to go, and I ended up on a narrow, cobblestoned street, in front of a half-burned synagogue with smashed-out windows.

It felt like I had been there before. The feeling was strong, palpable, like a childhood memory – a memory that was just outside the realm of my consciousness.

I eventually returned to Canada and tried to lead a normal life. But something always clawed at the back of my consciousness, pushing me toward a Jewish path. I lived along Bathurst street, in a predominantly Jewish neighbourhood. I began to read books on Judaism and spirituality. Ten years went by since I first thought of undergoing a formal conversion to Judaism, but something always held me back – I first wanted to discover the truth about my father, my family’s past. I had to know our own past in order to go forward.

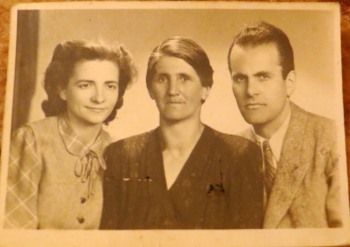

During a visit to my paternal grandmother’s village in Transylvania, I tracked down relatives, old family friends and neighbours, and asked questions. At my uncle’s house, among my deceased grandmother’s possessions, I discovered a box of mementos and photographs that I’d never seen before. The box was marked with the Jewish surname “Kohan” – the Hungarian version of Cohen. I finally began to believe that my suspicions had been true, and that my father had actually been Jewish.

Back in Canada, I ordered a DNA kit from 23andme, sent in my saliva sample and waited for a month to receive my results. When they came in, it was a surreal experience – one of the most significant days of my life. To realize that after so long, what I had suspected was actually true! I burst into tears of joy, knowing that I was no longer alone – at last I had a past, a history. And well over 20 relatives in the 23andme database with the surname Cohen, some of whom offered their help in piecing together our common ancestry.

Part of my conversion essay:

In my soul, heart and mind, Judaism is more than a religion for me. It’s a shared history, a genetic memory, a family and a connection that has always been just outside the realm of my consciousness, yet was always there. The more I learned about Judaism through my study, the more I felt my bond to the past grow stronger.

My father’s denial of his religion and heritage was like an invisible wall that kept me from my past. But with each day and each hour, the wall becomes increasingly transparent. The bricks fall apart and I begin to see a glimpse of something beautiful and mystical on the other side. The shadows of those great-grandparents and the whispers of their lives comes through to me, through me, and out into my very own existence.

I have had thousands of Jewish ancestors from Poland, Russia, Galicia, Ukraine and Romania, whose truth, lives and stories have been wiped off in only two generations. One hundred years. That is all it took to wipe out my family’s connection to their own lineage and heritage.

I look at the world and wonder how many others walk around unaware that the blood of Sephardic conversos or Ashkenazim forced to hide their religion runs through their veins.

I aim to reclaim that heritage.

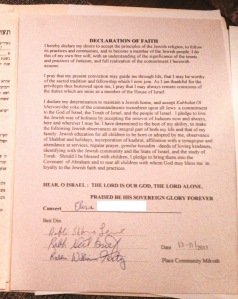

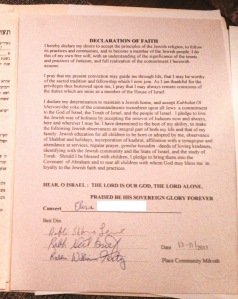

“Please read your Declaration of Faith for us, Elisa.”

I stood up and read the piece of paper which I had practically memorized over the past year.

Left: my declaration of faith. Centre: my favourite photo of me & my father. Right: grandmother Ana with her husband.

Afterwards, they asked me to sign it and I did so, then handed it back to them. I answered several questions related to holidays and ritual, and recited a couple of prayers. Then one of the rabbis asked me more about my father’s family. “Did you know the biggest group of immigrants to Israel after the war were from Romania?”

I hadn’t known this, and he smiled at me warmly and told me a story about his friends who had come from the same part of Transylvania as my father. Then our conversation touched on the Holocaust, and I mentioned the profound experience I’d had in my twenties when I visited Europe’s biggest concentration camp, the largest mass-murder site in the world.

Rabbi Fertig sat up. “You were at Auschwitz?”

“Yes,” I answered.

“What was it like?”

I gazed into the distance, recalling the summer of 2001 when I had backpacked across Europe, and how my journey to find my roots had led me to Auschwitz. “I went in the summer, when the grass was this high.” I said, lifting my hand to indicate waist-height. “It was a sunny day. A very beautiful day. The sun was high up in the sky, and there was such a vivid a juxtaposition of life and death. The grass was buzzing with crickets and frogs, filled with life….right up among those terrible barracks at Birkenau. I walked inside the barracks and felt that emptiness….the void, the echoes of the lives that had been lost there.”

Rabbi Levine stared at me for a long time. “So many millions perished in the Holocaust – and now you are returning to the fold.”

“I am but one drop,” I said quietly, my eyes filling with tears.

We all fell silent. After some time, Rabbi Brief asked me, “Have you chosen a Hebrew name?”

There was never any doubt in my mind what my Hebrew name would be – Elisheva, of course. The Hebrew version of my own given name. Better yet, it somehow ‘fit’ me. It felt more right than anything else.

“Elisheva Sarah.”

Rabbi Levine cleared his throat. “I am obliged to inform you that although a Conservative Beit Din is accepted by all conservative and affiliated denominations, some Orthodox will still refuse to see you as Jewish.”

I nodded. “Yes, I know this.”

“Do you have any questions for us?”

I hesitated. “Do you think….will I be accepted by a Reform synagogue?”

The rabbis looked at each other in amusement. “They’re going to love you,” the oldest of the rabbis answered. “Reform already recognizes you as a Jew because you have a Jewish father – so just based on the fact that you still went through this when you didn’t have to.”

Rabbi Levine peered into my eyes. “I read your conversion essay and I have to say it really moved me. You’re a very good writer. A very gifted writer.”

Something stirred inside me. Trying to fight back the knot in my throat, I said, “I’m working on a book to preserve the memory of those in my father’s village who have been forgotten. I want to do this for them – I’m the only one left who still carries their stories. Everyone else has passed.”

He nodded, and his eyes communicated such a deep empathy, such a sense of recognition and understanding, that I had to bite my lip to keep from tearing up. My eyes swept the room – the other rabbis were nodding, acknowledging me. I felt, in that moment, that they were seeing the real me – that part of my core I had kept hidden for so long. The vulnerability. The sadness and the truth of what I’d always known to be true. The real core of me.

Rabbi Levine pushed back from the table. “I am ready,” he said. He looked to the others: “I know it’s cutting this short, but I’m satisfied with this. I’m ready to make this woman Jewish.”

We walked out of the synagogue and around to the side of the building, where another door stood open. A tall, thin woman waited for us there, her hair covered under a beret-type hat. She beckoned us in and we shook hands. “Welcome Elisheva,” she said, smiling at me. “You can leave your coat and stuff here. I warmed up the water really well for you, and have everything set up for you. Come and let me show you around.”

I smiled back at her, and Carol’s eyes glided to my hair. “You have long, gorgeous hair,” she said with a smile, and I instantly read between the lines. The hair was going to be a problem. Making sure there were no tangles was going to be challenging enough. But then she added, “I’m concerned that it might float up when you submerge. Every strand has to go underwater.”

The rabbis sat down on a small bench in the narrow corridor that led to several rooms, including the one where Carol was leading me. It turned out to be a small but perfectly clean bathroom with a shower stall and all the toiletries one could imagine.

She closed the door behind us and pointed out everything, careful to inspect that I wasn’t wearing any nail polish. I started to remove my earring studs and put them in my backpack while she explained what I already knew – I was to scrub off everything once again, wash my hair thoroughly and brush it so there were no tangles anywhere. Then, when I was ready, to walk through another door wearing little bootsies to keep from slipping and only the towel.

“The Mikvah is completely private,” she assured me. “The rabbis will only listen to the submersion and I will be the only one in the room with you. They will hear you say the prayer, but they cannot see you. I am here to make sure your privacy is respected and I myself will not look at you – when you descend into the Mikvah I will hold up the towel and respect your privacy. You can rest assured that your privacy and modesty will be respected at all times. So take as long as you need to get ready, and I will be on the other side of that door.”

After she left, I tried to keep myself from shaking. To think that I was so close to the Mikvah I’d read so much about, so close to the completion of a journey that had taken me years to achieve!

The bathroom was spartan and super-clean. A shelving unit ran beside the sink, and everything I could possibly have forgotten was there: nail polish remover, cotton balls, extra soap, toothpaste, shampoo, dental floss, even a small vial of Air d’Temps perfume that I planned to spritz on after the ceremony was complete (but forgot to, in the ensuing excitement). As Carol had promised, two different kinds of combs lay ready to tackle my difficult hair. I chose the one with the wider-spaced teeth and bravely stepped into the stone shower stall.

The shower itself was as I’d expected, with the worst part being – of course – running the brush through my well-shampooed (but not conditioned) curls. Needless to say, when it was all said and done I lost more than my usual amount of stray hairs, possibly because I was so excited, nervous and emotional about the ritual to follow that I brushed a bit too impatiently and managed to snap off some more split ends.

The last thing to go were my contact lenses. The Mikvah rules were that nothing could stand in the way of the water immersing the body, not even contacts. I placed the case carefully on the sink ledge and wrapped the fresh white towel around my body.

Then I reached for the door handle and stepped into the other room.

The room was low-lit, with several pot lights illuminating only the water – which was as blue as the sea. The Mikvah was larger than I’d imagined, much larger than a Jacuzzi but not quite the size of a swimming pool.

Am I really here? Is this finally happening? I wondered, gazing in awe at the water that would soon immerse every bit of my being. It’s so beautiful.

I kicked off the bootsies and held still while Carol the Mikvah Lady inspected me in order to pick off any stray hairs that may have fallen down my back. I checked myself also and found an additional long hair that I handed her.

After she discarded the loose hairs, Carol came back and stepped behind me. “You can give me the towel and go in now,” she said, holding the towel I handed her up in front of her – as promised, to protect my modesty. Although I’d wondered what it would feel like being completely naked in front of a stranger, I realized that I didn’t feel embarrassed at all – this felt like such a perfectly natural, even maternal process.

I walked toward the Mikvah and began to descend the seven steps that led down to the main pool. I held the railing and stepped down the seven steps–each one representing a day in the Creation story. Then an unexpected challenge arose: by the fourth step I could already tell that the water was too deep. As in, over my head. I’m not a swimmer by any stretch, and have never managed to hold my own in the deep-end of a swimming pool. I would never be able to touch the bottom.

Over the past year I’d researched anything I could find about other people’s accounts of their conversion ceremonies, but had never read about the situation that confronted me now – being only 5’2” tall, by the time I reached the lowest step I was already immersed up to my chin.

I gazed into the shimmering depths of the main pool and realized, not without a fair amount of trepidation, that I would never be able to stand upright in it. The water was high enough to go over my head. Although I love splashing around in water, I’m not a swimmer and have never managed to tread water in the deep end of a swimming pool.

An irrational fear seized hold of my mind. Has anybody ever drowned in a Mikvah? I wondered, cringing inwardly at the ridiculousness of the question. Worst case scenario, Carol the Mikvah Lady was here, along with three rabbis on the other side of the wall partition. Surely somebody would pull me out if I didn’t resurface after a while, right?

My desire to become a Jew was now confronted head-on by my fear of drowning. The combination didn’t make for a particularly mystical experience. Did I want to convert badly enough to risk drowning? Would you rather live as a Christian or risk drowning to become a Jew?

The answer came hard and fast: YES. Yes, I wanted it that badly. Badly enough to jump off into the deep end, where the water towered above my head – not knowing if I would bob back up or sink right to the bottom.

Over the months that led up to this ceremony, I’d imagined this day to be a peaceful, holy, life-changing process. In a way, this was still partly true – with that tranquil blue water so warm and lovely, lapping at my skin, an aura of serenity had surrounded me. But suddenly another part of me was seized with fear. As anxiety mounted in my chest, I realized that in order to become a Jew I would have to conquer my terror.

I took a deep breath and tried to balance myself on the lowest step, which was really hard because the salt water makes you buoy about, making it impossible to keep your feet firmly planted onto the tiled ground.

“Are you ready?” Carol’s voice resounded behind me. “Take your time. When you’re ready, I want you to take a deep breath and jump away from the step. When you’re fully immersed under the water, lift your legs up so that you don’t touch the bottom to make sure that for an instant, you’re floating free.”

I sucked in a deep breath, steadied myself….and then stepped off the ledge. Water flooded into my eyes, mouth, over my head, and suddenly I was up again, sputtering and flailing toward the metal rail in the corner. I seized hold of it and clambered up onto the last ledge again.

Carol looked at my ungainly flop and smiled sympathetically. “We’ll have to do that one over again. Your hair didn’t go all the way under.”

Strands of my hair had floated to the surface since I hadn’t sank deep enough. “Does this happen a lot?” I asked her.

She nodded. “You’re very buoyant – we all are – so what you’ll need to do is really let go and try to jump up a little when you step away from the stairs. The force of you jumping up will ensure you submerge all the way down.”

I took another deep, shuddering breath, and felt determination flow through my entire body. I hadn’t come this far to allow fear to stop me now. I thought about my father, my grandmother, about our family friend Steve Bendersky and the relatives he’d lost in the war, about the numbers tattooed on his arm, about the heritage that had been denied me. I thought about the people who had been killed over the centuries for being a Jew, about all who had walked down this path before me as converts and embraced their Jewish neshama.

I had come this far. I was ready.

It still felt scary, taking that plunge – but I no longer cared about drowning. I wanted to leap as far into that water as I could, to take it all into my heart, to let it remind me of my strength and ability to survive anything.

I was enveloped in a cocoon of blueness and warmth – the perfect heat of a womb made of nature’s own waters that seemed to have always existed in and around me. I opened my eyes underneath the water which coated every pore of my being and thought, This is the day I was born. Back then, and then again today.

No sooner did that realization hit than a force propelled me upwards – the force of my own buoyancy. I hadn’t drowned after all. In fact, I felt stronger than ever.

Carol’s voice echoed throughout the small room: “Kasher!”

I repositioned myself on the last step, filled my lungs with air, and leapt up again. I sank down into the depths of the Mikvah and didn’t fight it this time – I gave myself to it in body and soul.

When I bobbed back up, Carol called out “Kasher” for the second time.

I half-swam back toward the steps, found my balance again and turned to face the blueness. This would be my third jump. When I came back up again, I would be a Jew.

“Take your time,” Carol said softly. “If you want to take a moment to say a silent prayer – just for yourself.”

I closed my eyes and felt tears brimming behind my eyelashes. I mouthed the words of the Shema silently, for everyone before me, and then again for myself – that I be worthy of that painful, beautiful legacy and that I might contribute toward making the world a better place.

And then I took the biggest leap of my life into the waters that had always waited there for me. I lifted my knees up to my chest and spread my arms out to my sides, and the Mikvah embraced me.

And as I came up to the surface as a Jew, Carol called out for the third time, “Kasher.”

My voice shook as I spoke the words of the final prayer, Shehecheyanu, a prayer uttered by Jews for two thousand years: “Barukh Ata Adonai, Elohenu Melekh Haolam, Shehecheyanu, Vekiyimanu, Vehigiyanu, Lazman Hazeh.”

As soon as I said the last word, “hazeh”, voices all around called out “Mazel Tov!” I heard the rabbis break out into applause from the other side of the partition carved in the wall, congratulating me.

I turned around and emerged out of the water slowly, its warmth following me. Carol was beaming at me, holding out the towel. “Mazel Tov, Elisheva.”

I pitter-pattered back to the bathroom where I was shaking as I toweled off, got dressed as quickly as I could, and put in my contact lenses once again. I was too impatient to take the time needed to blow dry my long hair, and as a result I was still dripping water when I re-emerged into the little room where everyone was waiting for me.

The rabbis surrounded me and put their hands on my shoulders, breaking into song. As they sang, said their blessings and gave me all the official conversion paperwork, tears started to course down my face. They sang the old traditional Siman Tov/Shalom Aleichem song and I just folded my arms across my chest and bit my lip to unsuccessfully stop myself from crying. The oldest rabbi, probably close to eighty, wrapped his arm around my shoulders in a way a father might comfort a daughter and as he held me while I cried, I felt the warmth of his joy – I had come home.

Above: me with rabbis after the ceremony. Right: a beautiful antique menorah – my conversion gift

In April 2015, a couple of years after my conversion to Judaism, I left for Romania in order to research my newest book, Remember Your Name. Because Bucharest is only a two-hour flight from Tel Aviv, I decided to make my first journey to Israel. I also fulfilled a secret wish I’d carried since my conversion – to go to the Western Wall and recite the Mourner’s Kaddish for my father.

It took me a lifetime to realize that my parents had been a by-product of their time – they had suffered so immensely that they had absorbed their oppression and passed it onto others. They made others suffer because that was the only way they could relate, after the pain they had endured. They hurt me because they themselves had been hurt. And then I too, as a child of their hatred, had tried my best to keep that light of hate alive – because I’d never known another way. So many scarred, wounded people have created the world we live in today, where suffering and oppression breeds brutality.

When I was in Israel, a new understanding flooded me – that my story doesn’t end with dissecting my own family’s hatred and buried identity. It doesn’t end with me converting to Judaism. I’m also digging back further into the history of hidden Jews and forced converts in Europe, and the internalization of hatred, the transformation of victim into oppressor. We see this everywhere today – oppressed becomes oppressor, persecuted people turn the brutalization they suffered into outward brutality – from the peasant workers’ 20th century revolutions that turned into communist dictatorships, to the Jewish-Arab conflict in the Middle East.

It’s all a vicious cycle. A cycle where hatred and religion-fueled intolerance supresses the spark of divine essence, the oneness, that connects all beings. A cycle of hate and judgemental intolerance so brutal that it’s pushed me toward feelings of worthlessness and thoughts of suicide for most of my adult life. Until I realized that the future of humankind doesn’t rest with governments and profit-driven policies but within us – that love is stronger than hate. Unity is stronger than division. Kindness reveals much more courage than brutality. That is where everyone’s G-d resides. In deeds of loving kindness. In recognizing our mistakes and showing forgiveness to those who harmed us. And in understanding that our differences are nothing in comparison to the beautiful light that shines within us all.

If you enjoyed the read, please consider dropping a dollar in my Patreon donation jar 🙂