Like many people, I discovered Elizabeth Bishop one evening in 2013 by scrolling through the newest offerings on Netflix, and choosing a movie called Reaching for the Moon. Unbeknownst to me, the story I watched that night would be the start of a new adventure – one that would lead me into foreign territory and transform my poetry in infinitesimal ways.

Much like Elizabeth’s own journey, in fact.

When she was 40 years old, American poet Elizabeth Bishop decided it was time to leave New York. She had reached a dead end both in her personal life (after a break-up with a long-time lover) and in her stagnant creativity, which resulted in a dry spell from publishing. Also struggling with alcoholism, Elizabeth longed for a new start, some way to rejuvenate her spirit and retrigger her inspiration. Receiving a fellowship from Bryn Mawr College was a godsend, and she decided that she would travel around the world.

When she was 40 years old, American poet Elizabeth Bishop decided it was time to leave New York. She had reached a dead end both in her personal life (after a break-up with a long-time lover) and in her stagnant creativity, which resulted in a dry spell from publishing. Also struggling with alcoholism, Elizabeth longed for a new start, some way to rejuvenate her spirit and retrigger her inspiration. Receiving a fellowship from Bryn Mawr College was a godsend, and she decided that she would travel around the world.

She telephoned the naval port and was told that the next available freighter was leaving for South America. Impulsively, she reserved a spot.

In November of 1951, Bishop boarded the Norwegian freighter S.S. Bowplate. Unbeknownst to her, the journey would change her life forever. The first port she arrived at was Santos, and what was meant to be a brief sojourn to visit with an old school chum from Vassar, Mary Morse, turned into an eighteen-year stay that would profoundly affect the rest of her life.

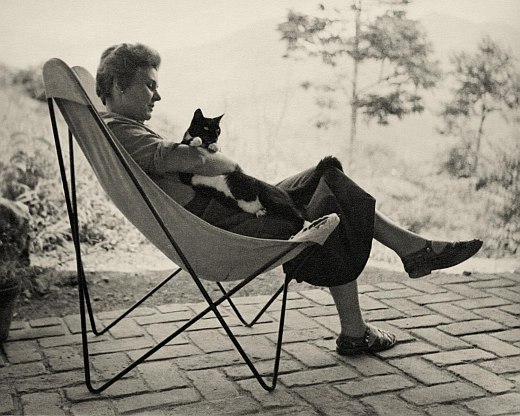

Toward the end of her vacation, Elizabeth fell ill from a violent allergic reaction to a cashew fruit and had to be hospitalized. While being nursed back to health, her relationship with Mary Morse’s Brazilian lover Lota deepened and grew more intense. Soon Lota de Macedo Soares, a self-taught architect from a prominent upper-class political family, broke up with Mary Morse and persuaded Elizabeth to stay in Brazil and move into Lota’s sprawling estate home at Samambaia, in the hills above Petropolis.

With Lota’s affection, Elizabeth flourished. It was there, amidst the lush jungle foliage and under Lota’s care, that Elizabeth wrote the poetry that would win her a Pulitzer prize and turn her into a world-renowned poet.

After watching Reaching for the Moon, I was convinced that I couldn’t stand Elizabeth Bishop. Her weakness, her repeated cheating on Lota, her complete dependence on alcohol as a way to relinquish personal responsibility. But out of curiosity, I wanted to see for myself if she was all she’s cracked up to be. Soon I would discover just how inaccurate the film was, and run into interviews that revealed director Bruno Barreto’s obsession with stylistic themes over historical accuracy. Like many biographical films, truth and historical fact was sacrificed to the artistic vision of a straight male director who’d never heard of Elizabeth Bishop before he read the script.

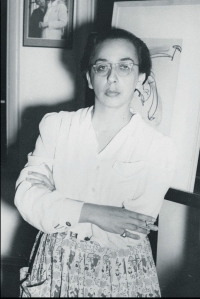

I would also discover that Elizabeth’s characterization in the film paled in comparison to the real person, both in physique and in spirit. Bishop didn’t resemble the tall, slender, cool, passive-aggressive character played by Miranda Otto. The real Elizabeth was short (only 5’4) and stout, intensely emotional, at times difficult, with an inner fire that was apparent to all who knew her. As the years progressed, her relationship with Lota became increasingly codependent. Paradoxically, the stronger she grew, the weaker Lota became. It would all come to a tragic end after Elizabeth traveled back to the US to teach at NYU and recently hospitalized Lota (against medical advice) decided to visit her in September 1967. On her first night in New York, Lota took an overdose of tranquilizers and fell into a coma, dying a few days later.

After Lota’s death, Elizabeth was shunned by her Brazilian friends and Lota’s relatives. She was forced to sell her Ouro Preto home and the Rio apartment bequeathed to her by Lota after Lota’s sister contested the will. Elizabeth soon realized that she had no future in Brazil without Lota and reluctantly moved back to the United States, eventually teaching at Harvard until her death in 1979.

Over the weeks and months to come, I would devour all Bishop-related material I could get my hands on. Soon I discovered that she had written much more than just poetry, and I was hooked. After Poems: North & South. A Cold Spring and Questions of Travel, I ordered her prose, correspondence, her incomplete, posthumously-published drafts and at least two biographies.

It started out as a hobby – reading all of Bishop’s writing. I spent an entire summer in my garden, reading book after book. Why? I still don’t know. Like Bishop’s feelings about Brazil, liking her didn’t come naturally. Some of her writing made me angry or befuddled me. I complained to my partner of how much I couldn’t stand Bishop-the-person, only to find myself returning to Bishop-the-writer’s work the next day.

It might sound crazy to most people. Why would I become inexplicably obsessed with a woman who died nearly forty years ago, a poet who was my complete antagonist? Why did I keep going down the Bishop rabbit hole instead of putting away her books? What kept me so engaged even as I complained about how weak and conflicted she was?

For all its flaws and incorrect depictions, Reaching for the Moon was a watershed moment for Bishop’s memory, leading many to look up her biography and (re)discover the small body of writing she had left behind. Until the film came out Bishop was a minor poet, largely forgotten by the masses and hardly ever studied in creative writing classes.

In all my writing classes over the years, Bishop’s poetry has never been covered. It’s easy to see why – shy and reticent to share the personal or make it political in an age when her compatriots (see Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton) found their stardom by turning their inner angst into poetic magic, she isn’t exactly an obvious choice for later generations, for youngsters who have been taught that the personal is political.

In contrast with the passionate, vibrant experimentation of the Beat Generation, Bishop’s classic approach to literature and her staunch avoidance to confront political and feminist discourse in her work rendered her an almost obsolete vestige of a repressed generation.

As a young poet, I was dazzled by the raw honesty of Kerouac, Ginsberg and Bukowski, swept away by Plath’s confessional brutality. Writers like Bishop and her idol, Marianne Moore, did nothing for me. I saw them as Vassar-reared, elitist upper class dilettantes who refused to address the sweeping changes of their time – they met in cafés and parlours to exchange and review each other’s couplets rather than discuss the Second World War that raged around them, the civil rights movement that brought equality to racial and sexual minorities.

Our poetic styles couldn’t be more different. I was as bold as Bishop was reticent; I challenged the establishment with the same ferocity she had retained while ignoring any criticisms of the government of her day. Her refusal to be included in feminist or women-only anthologies (underscored by the belief that it would somehow reduce her worth as a poet), her reluctance to openly come out as a lesbian even after the advent of gay liberation, all go against the grain of my own belief system.

Only in my late thirties could I have begun to appreciate the quiet strength that resides in Bishop’s poetry. I still can’t say that I like the woman on a personal level, but there is something about her that fascinates me. I’ve read passages of her letters (as addressed to Robert Lowell) that I found incensing, even borderline racist and contemptuous toward those less privileged than her – opinions no doubt amplified by being in the company of the Brazilian elites of the day. But there is also an overwhelming defiance in her writing, interweaved in equal parts with fear, hope and childlike wonder all at the same time.

Emboldened by my connection to Bishop’s work, I wrote my first villanelle One Europe after being inspired by One Art. And as soon as I submitted it, it was accepted for publication in Canada’s oldest poetry journal, CV2 (Contemporary Verse 2). I wrote a second poem, set in Brazil, and once again it attracted attention and a mentorship with a renowned Canadian poet. Clearly, Elizabeth Bishop’s influences on my own writing had produced results.

A year later, after I’d made my way through her entire correspondence and translations, going so far as to acquire some first editions of her books (including Life World Library’s Brazil), I realized that I had become a self-taught Bishop scholar. With that realization came the knowledge that I had to confront my own feelings and try to understand what it was about Elizabeth Bishop that both attracted and still repelled me. As it often is, people who trigger strong feelings in you are actually reflections of your own self, mirroring some part of self-identity that you refuse to see.

I realized how much I was like her. All the things I hated about her work were things I hated in myself. I wished she had been stronger, that she could have come out as a feminist or lesbian poet, but it took me years to allow my own identity to seep into my writing.

We live in an age that worships youth and carries the unspoken message that if you haven’t “made it” as a writer by your late 30s, you’re a nobody. Her success later in life, in spite of depression, personal struggles with a dark past and substance abuse, inspired and rejuvenated me in all those dark moments that come to all writers, when I felt down and hopeless.

And then came the day when I knew, more than anything, that I had to travel to Brazil.

I craved to see for myself the influences that had created the greatest phase of her career, and the years that she admitted were the happiest of her life. Brazil was where Bishop’s path took a new turn, where she produced work whose lasting power would outlive her.

I was 40 years old too. I often felt hopeless and burnt out. I would be lying if I didn’t admit that I wished to touch the same spark – that intangible, luminous magic – of inspiration that had struck Bishop. Some places have that effect, you know; just like some plants only bloom in certain soil, the fertility of creation comes easier in certain spots than others.

A view of Guanabara Bay and Flamengo Park – Lota’s vision. Taken from the top of Sugarloaf Mountain.

The 2016 Rio Olympics made it easier to travel to Brazil. The visa requirement was waved for the summer, security was at its best, and by booking far ahead I was able to line up affordable accommodations both in Rio and in Ouro Preto. Ignoring the dreadful headlines about killer Zika mosquitos and roving favela gangs, I spent most of August and the first week of September in Brazil, working on various projects which included researching the life of Elizabeth Bishop and Lota de Macedo Soares. Needless to say, I skipped the mosquito repellant and was not bitten once.

During my Brazil sojourn I wanted to stay a few days on Copacabana beach, just to take in the atmosphere, but didn’t realize that the hotel I’d booked was literally next door to Elizabeth and Lota’s old Leme apartment. Its street address and entrance might have been on Rua Antonio Vieira 5, but the balcony actually fronts onto Avenida Atlantica.

It was an amazing coincidence. Every day I’d look outside my window onto Leme beach, I realized it was essentially the same view they’d had back then. Every evening I went downstairs to have dinner and cashew fruit caipirinhas on the patio at Jaquina’s, which is actually on the main level of the same building. Lota’s apartment was the penthouse – which you can see on the highest floor. It’s the unit with the wraparound balcony and a walk-up to the rooftop (click photos to expand).

A few days after I arrived, I hired a driver and guide to take me up to Petropolis and the hilltops of Samambaia. Once the depressing urban jungle of Rio’s favelas gave way to mountainous vegetation, the road turned steep and narrow. I could only imagine how precarious it must have been back when Lota had to maneuver her Jaguar regularly on a winding, partially-unpaved road; now a two-hour drive, it took nearly twice as long back in the 1950s.

Here are some photos taken on that day. The actual Samambaia house is private property so we were not able to go inside, but the hilltop views reflect the fierce beauty of its surroundings. I also took photos of downtown Petropolis, Quitandinha Hotel (a Grand Hotel-type place where the millionaires, celebrities, movie stars and the elites of Petropolis congregated in the 1950s) and the Crystal Palace (click to expand photos).

During the last week of August, I flew to Belo Horizonte, the capital of the Minas Gerais region, and hired a car for the two-hour drive to Ouro Preto, which was even more spectacular, quaint and tranquil than I’d imagined. Once known as the biggest city in the New World, Ouro Preto is a UNESCO-designated World Heritage Site and the soul of Brazil’s 1700s gold rush. Its surrounding hills are stippled with gold mines and reddish clay earth.

It’s hard not to fall in love with its timeless, rustic beauty, which (oddly enough) reminded me quite viscerally of my grandmother’s Transylvanian village, where I spent many childhood summers. Safe and friendly, it’s easy to imagine living here for an extended stretch of time and just write. If I could afford it, I would return in a heartbeat.

Ouro Preto is a quintessential village with sloping cobblestone streets and several white stone bridges connecting different parts of town – a tapestry of eighteenth-century dwellings and ornate churches standing next to simple, whitewashed colonial houses. A sprawling main square dotted with baroque buildings next to an arts-and-crafts market.

The sunshine spills over an explosion of tropical plants sprouting prickly red flowers, then flows downwards to an abundance of purple-and-yellow wildflowers that grow in the sidewalk nooks. A smell of smoke and burning wood lingers after sunset, a dog barks in the middle of the night, the cackling rooster screeches at the crack of dawn.

A narrow, cobbled road connects Ouro Preto to its sister city Mariana, located a fifteen-minute drive away. High up in the hills overlooking the town, Elizabeth Bishop’s former home boasts an incredible vista that overlooks lush foliage, baroque churches and coppery-red shingled rooftops. In 1960 Bishop purchased a home here, at 546 Mariana Road; she called the house Casa Mariana (click on photos to expand).

It was bittersweet to say goodbye to Brazil, and I can only imagine how traumatic it must have been for Bishop to leave her adopted home, everything she had loved and lost here. But what made me sadder was how few people remembered Lota de Macedo Soares. Although her spirit is embedded in the beautiful Flamengo Park which circles Guanabara Bay, nobody I talked with in Brazil knew who I was speaking about.

My guide, a gay man who prides himself on having a history degree, announced that the park had been designed solely by Burle Marx. Even when I tried to impress upon him the significant work Lota did in the design and construction of the park, he (like others) wasn’t particularly interested in knowing about her. Even the small commemorative plaque in Aterro do Flamengo has misspelled Lota’s name and was never corrected. Sadly, in death Lota’s memory has been brushed aside and replaced with the names of powerful men who were determined (and arguably succeeded) in erasing her identity from the history of the city she loved and helped to transform.

Someday all our memories will be forgotten and lost – such is the fate of time and mortality. But I do hope that in the beauty of a blossoming garden, in the delicate verse of a poem that takes someone’s breath away, a shred of ourselves still remains.

Surely this is what Elizabeth and Lota would have wanted.

If you enjoyed the read, please consider dropping a dollar in my Patreon donation jar 🙂